Jennifer M. Jones - "Repackaging Rousseau: Femininity and Fashion in Old Regime France”

Jennifer M. Jones wrote this article in 1994. She is an Associate Professor of History at Rutgers University who focuses on European History. Overall the article gives an overview of the transformation fashion underwent in the eighteenth century, specifically at the end of the Old Regime and the beginning of the French Revolution.

Initially, Jones refers to Rousseau’s criticism of the way fashion “corrupted women’s taste” because during the Old Regime fashion tended to be too adorned and luxurious. Rousseau believed that women should instead use simpler materials and objects that subtly enhance their natural beauty. Rousseau did not see women as possible consumers since the fashion industry could so easily market “artifice rather than grace”(945), but he said that if clothing were to be made commercially, it would have to be made strictly by women.

Before the French Revolution started, elaborate dresses with ruffles, brocaded silks, and ballooning skirts that French women like Queen Marie Antoinette used to wear were considered fashionable. Simultaneously, in the 1780s a simpler style of dressing (like the one Rousseau encouraged) began to emerge. Women left behind the need for extravagant dresses and accessories, and instead wore “graceful white muslin vied with brocaded silks, natural hair and straw hats” (946). These changes in the accepted definition of fashion entailed a change in society’s definitions of femininity and womanhood.

Along with the changes of fashion in the 1780s came the emergence of fashion journals, the first fashion press that began dictating or setting the boundaries and meanings of future fashion. These journals, specifically the Cabinet des modes, were meant to be read by all those affected and interested in fashion, and aimed to organize the fashion culture solely on the basis of gender (and left behind categories such as rank, class, or privilege).

These French fashion journals simultaneously praised taste over luxury and excessive accessories. According to the editors taste consisted “particularly in the choice and assortment of colors, from which results an agreeable harmony that spills over onto the whole person” (959). This meant that fashion was available to everyone, not only those who could afford luxurious fabrics and jewels.

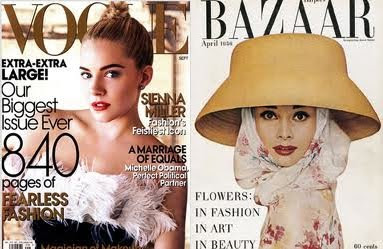

The fashion journals that emerged during this time served as the basis for the various fashion magazines that exist today. As Jones writes, "although one could discern some general guidelines as to how la mode operated, fashion must always remain, to some extent, an enigma..." (962) This idea is one of the main reasons fashion journals or magazines became so successful then, and are so successful now. The fashion press is definitely able to set the basic guidelines for taste, and therefore, for fashion.

No comments:

Post a Comment